My Husband Died Mid-Project — I Took Over His Business and Finished It Myself

The inspector ran his palm along the newly upholstered seat, then leaned into the cabin and sniffed like he expected trouble to confess. The engine idled with a rough, nervous sound. I stood outside the test bay at DVLA, Spintex, holding my late husband's folder so tightly my knuckles went pale.

Don't miss out! Get your daily dose of sports news straight to your phone. Join YEN's Sports News channel on WhatsApp now!

Source: UGC

"Madam, you said you're the owner?" he asked.

"Yes," I replied, even though the word still felt strange in my mouth.

He glanced at the paperwork again. Kofi Anane. My husband's name. The man who had died two weeks earlier in a hospital ward at Korle Bu, leaving me with grief on one side and an unfinished trotro refurbishment on the other.

Behind me, the lead mechanic, Yaw Boateng, whispered, "Please, talk calmly. Don't let them see fear."

Fear had already eaten my sleep for days.

The inspector climbed in, pressed the brake, tested the lights, and frowned at the dashboard.

Read also

UCC fresher cries out over small room assigned to him and his roommates: "The fan is even broken"

"This wiring," he said, tapping a spot near the steering column. "Who did it?"

"My team," I answered.

He looked at me sharply, like he wanted to laugh.

"You'll have to redo it," he said. "And the undercarriage needs attention. If you bring it back like this, you will fail again."

Again.

Source: UGC

That word hit me like a slap because we had already failed once.

The cooperative had paid a deposit. The driver, Alhaji Bawah, called me every morning: "Madam, where is my car?"

My husband's workers were waiting for wages. Suppliers were holding parts hostage. People kept saying, "Sorry for your loss," then immediately followed with, "So what are you doing about the vehicle?"

I swallowed hard and nodded at the inspector.

"Give me three days," I said.

And as I said it, I realised I was no longer begging life to spare me. I was bargaining with it.

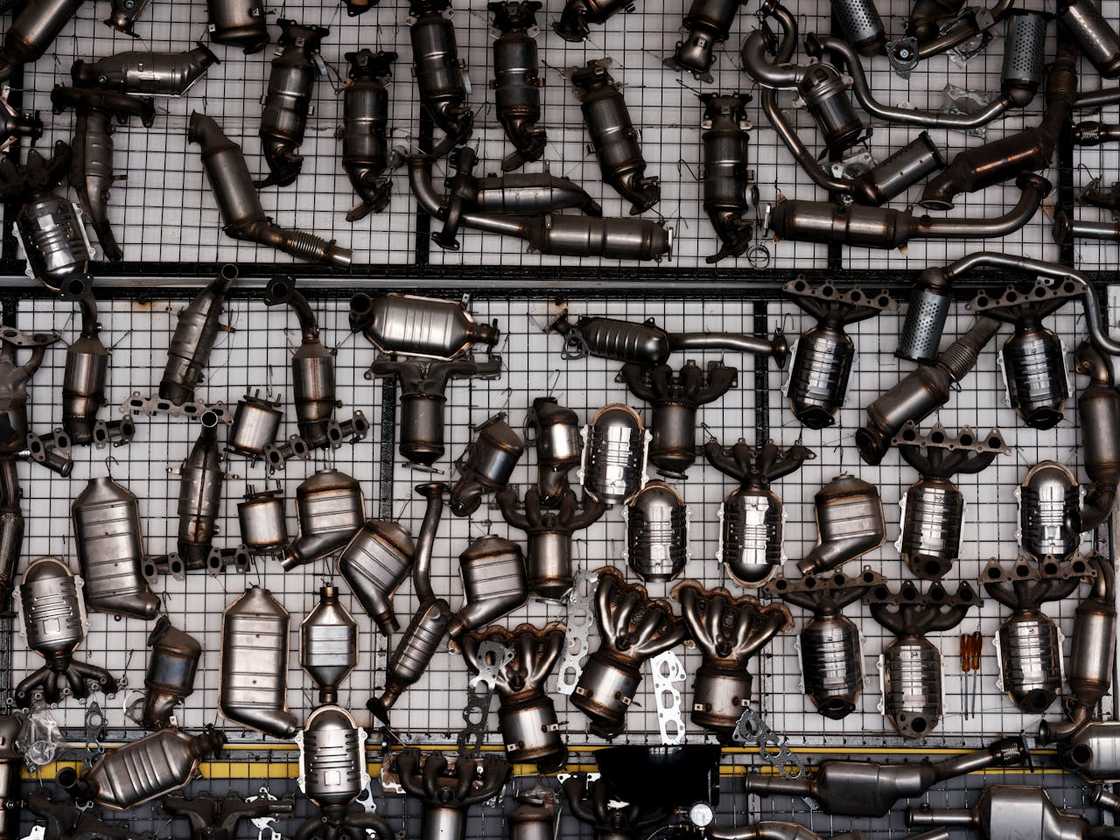

Kofi did not run a big company. He ran a small, stubborn dream.

By day, he worked a regular job; in the evenings and weekends, he managed a side operation in Abossey Okai, refurbishing trotro buses and old vans for transport owners. He loved the work because it mixed skill with pride. He would come home smelling of grease, hands dark with oil, and still smile as if he had built something holy.

Read also

Legon student appeals to ‘campus Hustlers’ to halt early morning sales, says it disturbs her sleep, video

Source: UGC

I supported him the way wives support projects that do not always make sense. I cooked late. I listened to talk about gearboxes and upholstery. I complained when he missed family visits. I also admired the way he kept showing up.

Then he fell ill.

At first, it exhibited a stubborn fever. Kofi insisted it was nothing. He drank herbal mixtures, tried to work through it, and joked about my worrying too much. Within days, he started losing weight. Within a week, his breathing changed, and his jokes disappeared.

We rushed to Korle Bu Teaching Hospital. Doctors moved quickly but spoke cautiously. Kofi held my hand and said, "It will be fine," with a voice that already sounded tired.

He died after a short illness, so fast that my mind refused to accept the pace of it.

I had no time to plan. No proper handover. No extensive conversation about what to do if things went wrong. No final instructions in a neat notebook.

Source: UGC

After the funeral in Koforidua, I returned to Accra carrying his phone, his wallet, and the weight of unfinished life.

Then Yaw came to our house and said the words that turned my grief into a deadline.

"Madam Ama," he said gently, "there is still that vehicle. The cooperative is waiting. They already paid deposit. The work is halfway."

Halfway.

That was the problem.

If I walked away, I would have to refund money I did not have. If I stepped in, I would enter a world I barely understood, where mistakes cost cash, reputation, and time.

And time did not care that my heart had just broken.

The first time I walked into Kofi's workshop at Abossey Okai after the funeral, the place felt like a stranger's house.

I recognised faces, but I did not recognise my role.

The workers greeted me politely, then looked past me, as if waiting for Kofi to appear and make everything normal again. Tools clinked. A radio played old highlife softly. The half-refurbished trotro sat in the corner like an accusation.

Source: UGC

Yaw wiped his hands on a rag and guided me around.

"We changed the seats," he explained. "We started the body work. The engine needs a tune-up. Wiring is not finished."

I nodded as if I understood.

In truth, I understood only one thing: this project had teeth.

That afternoon, a supplier, Mr Quartey, refused to release parts unless "the man himself" confirmed payment.

I told him, "My husband has passed. I am handling it now."

He sighed loudly. "Ei, sorry oo. But ma'am, business is business. I can't dash parts."

I felt heat rise in my face.

"It's not dash," I said. "We have a contract. We have a partial payment. I need the brake pads and the side mirrors."

"Bring cash," he replied. "Or bring Kofi."

The second problem came from inside the workshop.

Two workers cornered Yaw in my presence.

"Boss, what about our money?" one asked. "Kofi promised he would pay us after the next delivery."

Source: UGC

Yaw looked at me helplessly because he knew the job, but he did not control the cash.

I realised what I had inherited. Not just grief, but a fragile trust system built around my husband's voice.

That evening, I sat on my bed in our small flat at Dansoman with Kofi's notebook open on my lap. His handwriting looked confident, almost arrogant. Costs, deposits, measurements, supplier names, phone numbers. He had been running a small economy, and I had been living beside it without seeing it.

I made a choice that scared me.

I would finish the project.

Not because I wanted to play hero widow. Not because people would praise me. I would finish because I needed stability. I needed cash flow. I needed to stop living like the ground could open at any moment.

The next morning, I went back to the workshop with a cheap plastic folder, a pen, and a new voice.

Source: UGC

"We will do this properly," I told them. "I will pay what we owe, but I will also track every cedi. If we waste, we all suffer."

Yaw studied me carefully.

"Madam," he began, cautiously, "this thing is not easy. The cooperative people are not patient."

"I know," I said. "So let's be honest. What do we need to finish, and what can we cut?"

For the first time, the conversation became real.

We listed parts. We listed labour.

What had been paid, and what remained. I called the cooperative chairman, Mr Sarpong, and introduced myself.

"Sir, my husband died," I said, forcing the words out calmly. "I am completing the refurbishment. I need seven more working days."

There was silence, then he said, "Madam, sorry. But this vehicle is for work. If you delay, the driver loses income."

"I understand," I replied. "I will deliver. But I will not promise magic."

Read also

Here's what Mahama told Asake when he tried to lobby for Cyborg's release after firing a gun

Source: UGC

He agreed, not warmly, but practically.

Then the vehicle failed its first inspection at DVLA, Spintex.

The inspector pointed out wiring and undercarriage issues with the accuracy of someone reading my private fears aloud.

When we drove back to Abossey Okai, Yaw kicked a tyre in frustration.

"This is what I feared," he muttered. "They will laugh at us."

I looked at the trotro, then at my hands.

"We redo it," I said.

"But madam, it will cost."

"Then we negotiate," I replied. "And we cut what we can."

Yaw stared at me again, this time with something like surprise.

I expected to do all of this with Kofi's ghost hovering over my shoulder.

Instead, I did it with my own hunger for survival pushing me forward.

One afternoon, I sat with Mr Quartey in his shop, surrounded by spare parts and men who looked like they could smell weakness.

Source: UGC

"I can't pay full today," I told him. "But I can pay part now and the rest on delivery. Here is the cooperative contact. Here is the contract."

He raised an eyebrow. "Madam, are you sure you can deliver?"

"I am sure I can work," I said. "And I am sure I can remember who helped me when I was building."

He laughed, then surprised me by reducing the price slightly.

"You talk like Kofi," he said, softer. "He was stubborn too."

At the workshop, I started keeping the books properly. I wrote down labour hours. I recorded every purchase. I asked questions without apologising for not knowing. I sat with Yaw as he explained wiring as if he were teaching a student.

At first, he still spoke to me like he could swap me out at any moment.

"Madam, when your husband's brother comes, we will show him," he said once.

I looked him in the eye. "No brother is coming. I am here. Talk to me."

Source: UGC

After that, Yaw's tone changed.

He began calling me before making decisions.

"Madam Ama, the upholstery man wants extra for the headrests. Should we agree?"

"Negotiate," I said. "If he refuses, we simplify."

Some workers complained when I cut small luxuries that Kofi would have approved.

"Madam, this is not how boss used to do it," one said.

"I am not your boss," I replied quietly. "I am the one trying to pay you."

That sentence tasted bitter, but it also felt true.

Some nights, I still cried for Kofi. I still woke up reaching for his side of the bed. In the daytime, my identity shifted without permission.

I stopped being "the widow managing chaos".

I became the person making decisions that kept the wheels moving.

I did not recognise her at first.

Source: UGC

We fixed the wiring properly. Yaw brought in an electrician he trusted, and I agreed to pay him on a strict timeline. We reinforced the undercarriage, replaced the faulty parts, and tested the vehicle on rough roads until the suspicious sounds disappeared.

Three days later, I returned to the DVLA test site, Spintex.

This time, I wore a simple black dress and flat shoes, with my folder organised like armour. Yaw stood beside me, quieter than before.

The inspector checked again. He tested the brakes. He flicked the lights. He looked under the vehicle, then climbed back out.

He stared at me for a long moment.

"It's better," he said finally.

My heart hammered.

He nodded once. "You pass."

I did not scream. I did not jump. I just closed my eyes and breathed like someone who had been underwater.

Source: UGC

We delivered the trotro to the cooperative yard near Circle. The driver, Alhaji Bawah, walked around it slowly, touching the paint, bouncing on the seats.

"Madam, you did well," he said, genuinely.

When the final payment came in, I paid the workers first. I cleared the supplier balances. I kept a small profit, just enough to feel like a foundation.

Then I did something people did not expect.

Read also

My Girlfriend Used My Account to Insult Women — I Took Back Control and Changed Every Password

I closed the business.

Not because I failed. Because I finished.

I knew I could not keep running it long-term with my grief still raw and the emotional weight of every tool and corner. I also knew I had gained something valuable: knowledge, contacts, and proof that I could handle pressure.

I moved from Dansoman to a smaller place closer to the industrial areas, near Kaneshie, to reduce transport costs. I started taking short‑term work managing logistics for other garages. I sourced parts, coordinated schedules, handled paperwork, and kept simple accounts.

Yaw stayed in my life only as a professional connection. He sometimes called for a supplier contact, and he always spoke with respect.

Source: UGC

"Madam Ama," he said one day, "you surprised all of us."

I did not correct him. I surprised myself, too.

Later that year, I enrolled in a technical management course in Accra, the kind that teaches operations, budgeting, and basic mechanical project planning. I did not feel healed. I still missed Kofi like an ache that lived in my bones.

But I felt grounded.

I felt like someone who could stand in the middle of loss and still build something solid.

Grief does not wait for your calendar.

It does not care about contracts, deposits, or deadlines. It arrives, takes what it wants, then leaves you to manage what remains.

When Kofi died, people expected me to crumble, and I did crumble, privately, in the quiet places where no one needed answers. But public life still demanded decisions. Workers still required wages. A cooperative still needed a vehicle. Bills still showed up on time.

I used to think strength meant being fearless.

Now I know strength can look like shaking hands that still sign the papers.

Source: UGC

It can look like a woman asking questions she feels embarrassed to ask, because she refuses to fail silently. It can look like choosing stability over pride, and boundaries over chaos.

Finishing that project did not bring Kofi back. It did not give me closure. It did not turn pain into a neat lesson.

Read also

My Boyfriend Insulted My Culture in Front of My Relatives — I Broke Up With Him Mid-Celebration

But it gave me something I needed more than a motivational speech.

It gave me evidence.

Evidence that I could learn fast. That I could negotiate. Proof that I could lead, even in a space that never expected my voice.

I did not finish that trotro to prove love.

I finished it because I needed a future.

And in doing so, I discovered a version of myself I did not know existed.

So here is the question I sit with when life feels unfair again: If you lost the person who always handled things, would you collapse, or would you discover what you can carry?

This story is inspired by the real experiences of our readers. We believe that every story carries a lesson that can bring light to others. To protect everyone's privacy, our editors may change names, locations, and certain details while keeping the heart of the story true. Images are for illustration only. If you'd like to share your own experience, please contact us via email.

Source: YEN.com.gh