Family Shamed My Deaf Son — Now He Teaches Music and Earns More Than His Uncles

The silence in our compound was so heavy it felt like a physical weight, but the music coming from Mawuli's flute was heavier still. It was the day of my late husband's final memorial, and the air was thick with the scent of roasted goat and the judgmental stares of a hundred relatives.

Ghana’s top stories, now easier to find. Discover our new search feature!

Source: Getty Images

'Stop that noise!' Uncle Kosi's voice cut through the air like a cutlass. He didn't just speak; he spat the words. He stepped toward Mawuli, who was sitting on a low wooden stool near the grain store.

Mawuli didn't flinch. He couldn't hear the command. He was lost in the vibration of the wood against his lips, his eyes closed, his fingers dancing over the holes of the flute Moses had left behind. To Mawuli, the world was a series of rhythms he felt in his chest, not sounds he heard in his ears.

'Are you deaf and stupid?' Kosi roared, snatching the flute from my son's hands.

Read also

Nanyah Music's neighbour shares observation about her residence after she died from snake bite

The sudden pull nearly pulled Mawuli off the stool. The music stopped abruptly. The silence that followed was worse than any scream. Mawuli looked up, his eyes wide, searching Kosi's face for the reason for such violence.

Source: Getty Images

He saw the anger in the twisted mouth, the vein throbbing in the uncle's neck. He didn't need ears to understand he was being hated. 'I told you, Dzifa,' Uncle Wycliffe stepped forward, adjusting his expensive-looking coat.

'This boy is an embarrassment to the family name. People are laughing. They say the widow of Moses has a son who blows into sticks like a madman.' I stood up from the mat where I had been sorting beans. My heart was thumping against my ribs. 'He is not a madman. He is expressing what is inside him.'

'What is inside him is a curse!' Wycliffe shouted, loud enough for the neighbours to hear over the fence. 'A deaf child is a half-finished person. You waste money on flutes while we struggle to keep the family legacy alive. Look at him. He can't even plead for mercy because he has no tongue for it.'

Read also

"He'll come back here": President Mahama speaks about IShowSpeed's shea butter massage in Ghana

Source: Getty Images

Mawuli reached out for his flute, his hands trembling. Kosi threw it into the dirt. 'If I see this stick again, I will burn it. A funeral is for mourning, not for the circus acts of a broken boy.'

I looked at my son, who was now kneeling in the dust to retrieve his only treasure. I looked at my brothers-in-law, the men who were supposed to be our pillars. In that moment, the shame they tried to heap on Mawuli moved from his shoulders to mine, and then it turned into something cold and sharp.

Something that would stay with me for a decade. The trouble had started years ago, when Mawuli was only two. A fever had come in the night, a fire that scorched his insides and stole the music of the world from him. Before the fever, he would mimic the birds. After the fever, he was a silent observer in a loud world.

Source: Getty Images

When Moses died in a boating accident on the lake, the protection I had disappeared. In our village, a widow without a 'whole' son is seen as a person with one foot in the grave. My brothers-in-law, Kosi and Wycliffe, took over the family land. They took the cattle.

They made the decisions. When it came time for school fees, they sat me down under the mango tree.

'Dzifa, be reasonable,' Kosi had said, picking his teeth with a twig. 'Mawuli cannot hear the teacher. Why throw good money after a lost cause? Let him stay here and fetch water. He could learn to weave baskets. But school? That is for children with a future.'

I saw the way they looked at him, as if he were a broken chair that stayed in the corner because no one had the heart to throw it out yet. They called him 'the one who is half-gone'.

But Mawuli was more present than any of them. He began to follow me to the market, where I sold smoked fish and kontomire. He would sit by the water's edge and watch the ripples. One evening, he found his father's old flute in a trunk of clothes.

Source: Getty Images

He didn't know what it was for at first. He just liked the smoothness of the wood. Then, he saw a man playing a recorder at a wedding. Mawuli watched the man's mouth. He watched the way the man's chest rose and fell. Back at home, Mawuli began to experiment. He would press his throat against the wooden cylinder.

He would blow and feel the hum in his teeth. He wasn't playing notes; he was playing sensations. I watched him for hours. He would place his bare feet on the ground to feel the vibrations of my footsteps. He learned the rhythm of the rain on the corrugated iron roof by the way the floorboards trembled.

He was teaching himself a language that had no words. The neighbours weren't kind. 'Dzifa, your son is haunting the village,' they would say. 'That whistling is like the wind through a graveyard. Tell him to stop.' I didn't tell him to stop. I sold extra crates of tomatoes.

Source: Getty Images

I skimmed a few cedis from the fish money. I bought him a better flute, one made of polished dark wood. When the relatives found out, they were livid. 'You are feeding a delusion,' Wycliffe warned. 'He will grow up to be a beggar, and you will be the one who made him one.'

The years that followed the funeral incident were the hardest. I stopped taking Mawuli to family gatherings. I grew tired of the way the cousins would throw pebbles at him while he practised, laughing when he didn't turn around because he couldn't hear them coming.

'Why do you hide him?' Kosi asked me on a market day. 'I am not hiding him,' I replied, my voice steady. 'I am protecting you from your own cruelty. You don't deserve to see his progress.' 'Progress?' Kosi laughed, his belly shaking. Is he suddenly hearing the angels?

Source: Getty Images

He is a burden, Dzifa. When you are too old to sell fish, he will be the weight that sinks your boat.' Mawuli and I carved out a life in the margins. Every morning at 5:00 am, before the village woke up, he would go down to the river. He would sit on a flat rock and play to the rising sun.

He had learned to 'see' music. He watched the way the reeds swayed in the breeze; that was his tempo. He watched as the light hit the water, which was his melody. He practised until his fingers were calloused and his breath control was so steady he could hold a single, vibrating note for nearly a minute.

He started playing at gravesides. Not for us, but for strangers. A family from the next village had heard of 'the boy who plays the silence'. They lost a daughter and wanted something different.

Mawuli stood by the open earth and played a song so mournful, so deep, that even the birds seemed to stop. He felt the grief of the mothers in the way they stomped their feet; he turned that vibration into a low, humming tune that moved through the ground and into the soles of the mourners' shoes.

Source: Getty Images

They gave me GH₵150. It was more than I made in two days at the market. When Wycliffe heard about it, he came to the house to demand a 'family tax'. 'The boy is using family talent,' Wycliffe said, reaching for the money.

'No,' I said, standing in the doorway. 'He is using the talent you called a curse. This money is for his books. He is learning to read music from a manual I bought in the city.' 'He can't read music if he can't hear it!' Wycliffe spat.

Read also

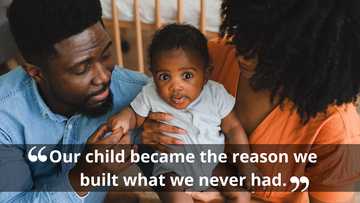

Both From Unstable Homes — Having a Child Forced Us to Build Daily Safeguards to Break the Cycle

'He hears it better than you hear the truth,' I said, and I shut the door in his face. It was the first time I had ever closed a door on a male relative. The village whispered that the widow had finally lost her mind. The turning point came during the height of the dry season. A large burial was taking place for a local elder, and many visitors had come from the capital.

Among them was a woman named Dr Sena Adzoa. She worked for a large international foundation that focused on inclusive education. Mawuli was playing near the river, far from the main ceremony, as was our custom to avoid trouble.

Source: Getty Images

But the wind carried the sound. Dr Okello walked away from the dignitaries and followed the music. She found a young man, tall and lean, eyes closed, playing a flute with such technical precision it rivalled professional orchestras. She stood there for ten minutes.

When Mawuli finished, he opened his eyes and saw her. He didn't startle. He nodded. She tried to speak to him. He pointed to his ears and shook his head, then pointed to me, sitting on a log nearby. 'He is deaf?' she asked, her voice full of disbelief.

'Since he was two,' I said. 'His timing...' she whispered. His phrasing is perfect. How does he know?' 'He feels it,' I explained. 'He watches the world breathe, and he breathes with it.' She didn't leave that day. She stayed to talk.

She told me about a programme in Kumasi that trained 'adaptive' music teachers, people who could teach the arts to those with disabilities. Two weeks later, she returned with a team. They brought a sign-language interpreter, a man named Sam.

Source: Getty Images

For the first time in his life, Mawuli saw someone whose hands moved with the same rhythm as his flute. Sam signed to Mawuli: 'Your music is a bridge. Do you want to show others how to cross it?' Mawuli's face transformed. A smile broke across his lips that I had never seen before, a smile of recognition.

The village watched as a white van with 'International Arts Initiative' printed on the side pulled up to our humble house. They watched as Mawuli loaded a small bag and his collection of flutes. 'Where is he going?' Kosi demanded, standing by the road.

'Is he being taken to a home for the disabled?' 'He is going to a university workshop,' I said, unable to hide the pride in my voice. 'He has a scholarship.' 'A scholarship for a whistler?' Wycliffe mocked. 'They will send him back in a week when they realise he is a stone.'

However, he didn't return in a week. He stayed for six months. Then a year. Then three. Every month, Mawuli sent money back to me through a mobile transfer. Initially, it was in small amounts. Then, it grew. He was no longer just a student; he was a consultant.

Source: Getty Images

He was helping design a curriculum for deaf musicians across East Africa. The radio stations started playing recordings of his compositions. They called him 'The Silent Maestro'. In the village, the mockery began to give way to a confused silence.

The day Mawuli returned for a visit, he didn't come on a dusty bus. He arrived in a clean, silver vehicle that he had purchased himself. He was dressed in a sharp suit, and he carried a bag of gifts for me: fine clothes, good coffee, and a new stove.

Word travels fast in a lakeside town. Within an hour, Kosi and Wycliffe were at my gate. They didn't come with insults this time. They came with hunched shoulders and forced smiles. Kosi looked at the car. He looked at Mawuli, who was signing rapidly to me about his flight from a conference in Accra.

Mawuli looked at his uncles, his expression neutral. He remembered the funeral. He remembered the dust. He remembered the snatched flute. 'Dzifa,' Kosi began, clearing his throat. 'We have had a tough season. The rains failed. Wycliffe's eldest son has been sent home from secondary school due to a lack of fees.

Read also

Efia Odo's throwback post on how Ground Up messed up Kwesi Arthur resurfaces amid controversial allegations

Source: Getty Images

We thought... since Mawuli is doing so well... since we are all blood...' I looked at Mawuli. I didn't need to sign for him to understand the energy in the room. He could see the desperation in his uncle's eyes, the same eyes that used to look at him with disgust.

I felt a surge of bitterness. I wanted to scream. I wanted to remind them of the pebbles and the names. I tried to tell them to go and find the 'half-finished boy' they used to know. Mawuli stepped forward. He took out a leather wallet. He pulled out a stack of notes that was more than Kosi saw in three months of farming.

Kosi reached out, his fingers twitching. Mawuli held the money for a moment, then he handed it to me, not to Kosi. He looked at me and made a series of signs. 'He says,' I translated, my voice cold, 'that he will pay the school fees for the children.

However, the money will not come into your hands. He will go to the school himself and pay the bursar directly.' Wycliffe looked offended. 'Do you not trust your own brothers?' 'Trust is earned,' I said. 'Mawuli knows that better than anyone.

Source: Getty Images

You told him he had no future. Now, he is the only one providing a future for your children.'Mawulio signed again. 'He also says,' I continued, 'that he forgives you. Not because you deserve it, but because he does not want to carry the weight of your hate anymore. It interferes with his music.'

The uncles stood there, shamed in the very compound where they had once shamed a child. They took the help, but they couldn't look Mawuli in the eye. They left quietly, walking back down the dusty path, two men who had been outgrown by the boy they tried to stunt.

That evening, Mawuli and I sat on the porch. The sun was dipping into the lake, turning the water into a sheet of hammered gold. Mawuli took out his professional flute, made of silver and wood. He began to play. The music was different now.

It wasn't just a hum; it was a conversation. It was the sound of a man who had found his place in the world. I watched him and thought about the journey he had taken. People often ask me how a deaf boy became a master musician. They believe it is a miracle. But I know the truth. It wasn't a miracle. It was a refusal to accept the labels the world tried to pin on him.

Source: Getty Images

The village now calls him 'Nkyerɛkyerɛfoɔ' - Teacher. When he walks through the market, the same people who used to mock him now pull their children aside to let him pass. They point at him and say, 'That is the man who teaches the world to hear through their hearts.'

I look at my son, and I see a whole person. More than whole. He is a man who turned silence into a symphony. The lesson I learned is simple: The people who try to silence you are usually the ones who are most afraid of what you have to say.

As I watched Mawuli's fingers move, I felt the vibration of the music in the floorboards beneath my feet. It felt like a heartbeat. It felt like home. I turned to him and sighed, 'Are you happy?' He put down the flute, looked at the horizon, and sighed back: 'I am heard.'

Source: Getty Images

The story of Mawuli and Dzifa serves as a reminder that human potential is not defined by our physical senses but by our internal resilience. In many cultures, disability is wrongly equated with a lack of value, leading families to 'hide' or neglect children who could otherwise flourish with the proper support.

Mawuli's success didn't come from ignoring his deafness, but from finding a unique way to work with it. His uncles saw a 'broken' boy; the world saw a visionary.

If you were in Dzifa's position, would you have shared your son's success with the family members who once shamed him, or would you have walked away entirely?

This story is inspired by the real experiences of our readers. We believe that every story carries a lesson that can bring light to others. To protect everyone's privacy, our editors may change names, locations, and certain details while keeping the heart of the story true. Images are for illustration only. If you'd like to share your own experience, please contact us via email.

Source: YEN.com.gh